Yokai You Didn’t Know You Had to Worry About

Wraith wrists, slithering sashes, and killer clams, oh my! Explore some unexpected terrors through a selection of yokai from Toriyama Sekien’s (1712-1788) The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past (Konjaku Hyakki Shūi, c. 1781).

Madison Folks

10/23/20254 min read

From vengeful ghosts to mischievous spirits, Japanese folklore brims with tales of terror and trickery. Edo-period (1603-1868) audiences enjoyed tales of these supernatural entities—known generally as yōkai—through art, literature, and theater. As each art form inspired the other, these stories of the supernatural reverberated through woodblock print interpretations, kabuki stage effects, and illustrated books. Today, yōkai remain alive in these familiar forms as well as fresh evolutions for the contemporary world—whether inspiring a new species of Pokémon or engaging anime and manga audiences through supernatural series like Dandadan. However, some of the more obscure yōkai require a deeper dive into history. For this task, we can look to one of Toriyama Sekien’s (1712-1788) encyclopedias of monsters, The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past (Konjaku Hyakki Shūi (今昔百鬼拾遺), c. 1781).

As a flame flickers high from an elaborate candlestick, you take in the storage room. You notice a floral kosode draped across a table, flowing silk amidst a jumble of forgotten objects. The fabric flutters—perhaps a breeze? Yet you fear it’s something a bit more supernatural as a pair of delicate arms emerge, fingers reaching towards you from the narrow sleeves.

There are a variety of tales related to the kosode-no-te, but this yōkai can be understood through primary lenses. In the first, this spirit is simply a kosode (a type of kimono) that has been possessed. Such yōkai are known as tsukumogami—tools or items that have gained a spirit and self-awareness. This transformation is tied to the age of the item, typically around 100 years. When an object is thrown out just before its transformation, it becomes enraged and becomes a monster. From tickling the wearer to strangling them, the actions of the kosode-no-te can range from silly to deadly. In the second, more culturally-situated reading of these ghostly hands, the kosode-no-te reflects the difficult lives of courtesans. Whether reaching out to potential customers with hope of buying one's freedom, restless due to a wrongful death, or grasping for a brief taste of life from beyond the veil, these kosode-no-te are unsettled human spirits born from a life of strife.

Wraith Wrists: Kosode-no-te (小袖の手)

Toriyama Sekien, "Kosode-no-te" from The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past, v.2 (Mist), c.1781, illustrated book, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York.

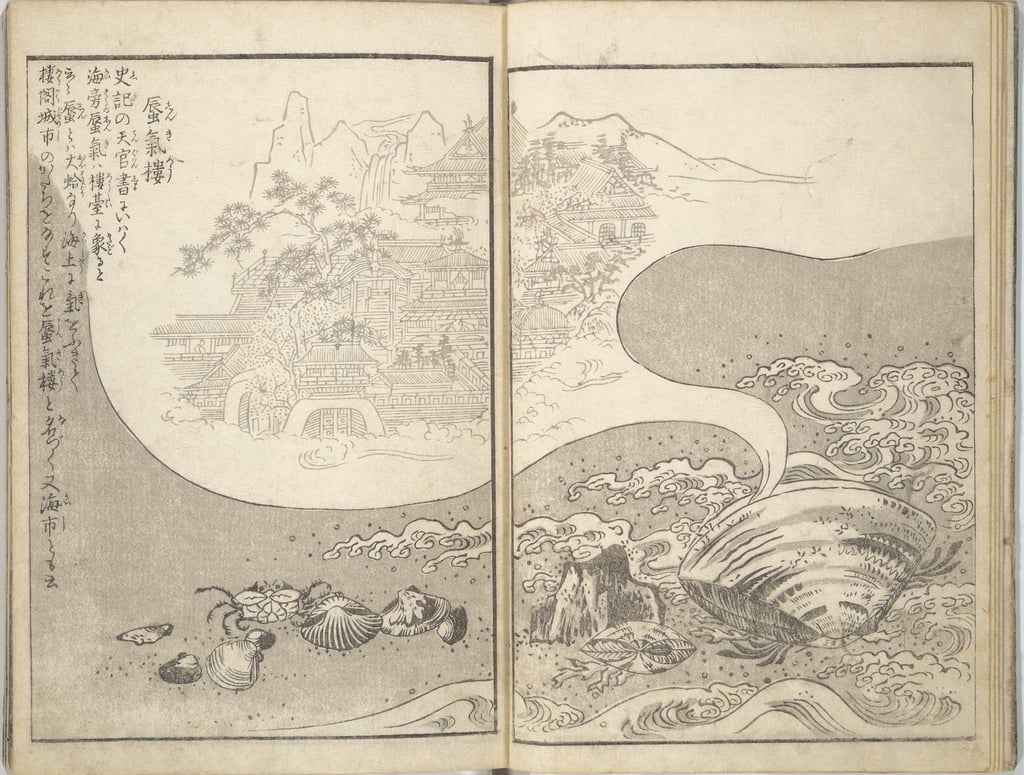

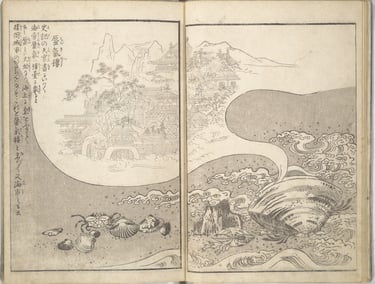

As your boat glides across the open ocean, it's suddenly hard to believe your eyes. The towering palaces and lush gardens of a brilliant city rise from the distant horizon. Though your navigation system assures you that no city should be visible from these bearings, you can’t dissuade yourself of the existence of this place. It looks far too real! However, in this case, it’s really best to trust your technology.

Meaning “mirage,” the term shinkirō refers to an enormous magical clam that rises up from beneath the waves, opens its shell, and exhales a mirage of a fantastic city just out of reach. While sailors today have GPS to keep them on course, Edo-period (1603-1868) sailors faced a greater risk of being led astray. Some sources suggest that the city projected by the shinkirō is none other than the home of Ryūjin, the dragon king that lives on the sea floor.

Killer Clams: Shinkirō (蜃気楼)

Toriyama Sekien, "Shinkirō" from The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past, v.1 (Clouds), c.1781, illustrated book, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York.

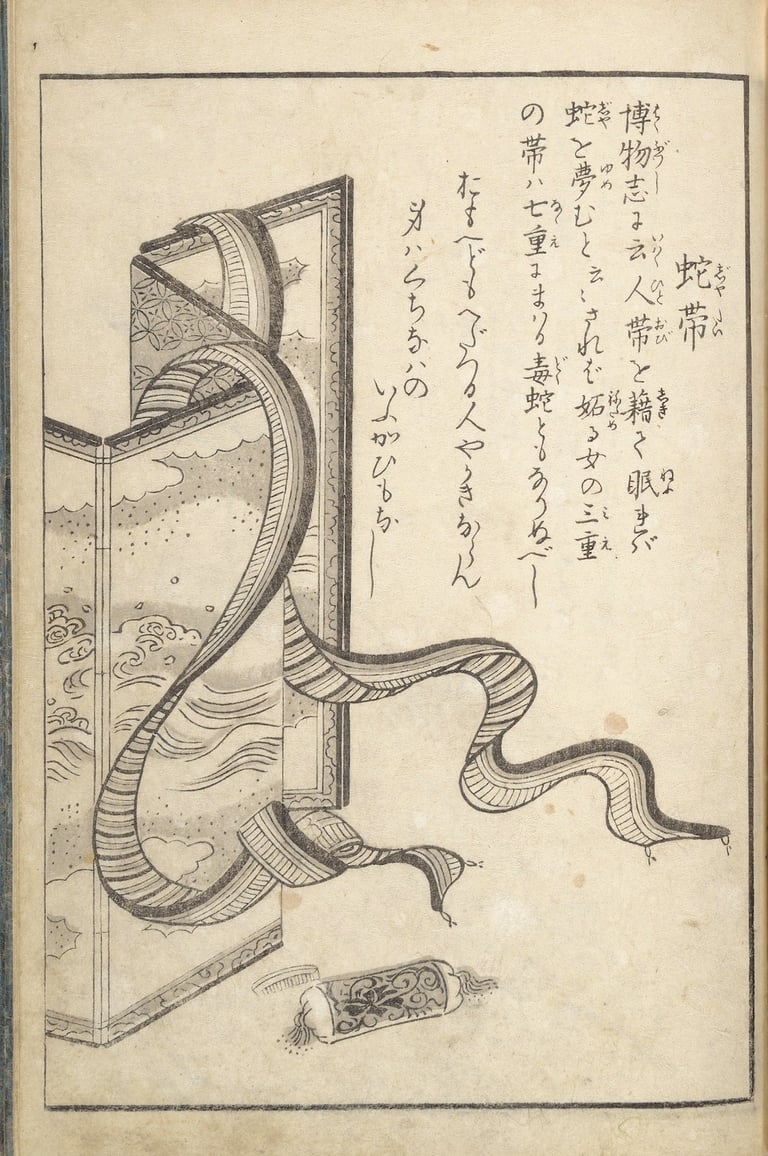

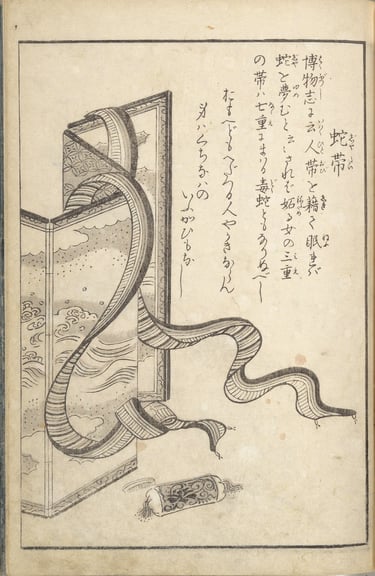

After a long evening you untie your obi (sash worn around the waist with a kimono) and toss it over a nearby screen. You settle your head onto a pillow, mind racing. Perhaps irritated with a lover’s wandering eye or a rival’s besting of you, the green tinge of jealousy colors your mind and saturates your subconscious. As you drift off to sleep, your obi awakens, slithering into the air like a snake.

This yōkai brings together folk beliefs and word play. The text in the top right of this composition says that a man sleeping with an obi will dream of snakes, while a jealous woman will see her obi turn into seven snakes. It is said that the jatai's name (translated literally to "snake obi"), derives from word play with the words jashin (邪心), or “evil heart,” and jatai (蛇体), or "snake body.” The evil heart in question can be understood as a jealousy that animates the obi as it seeks out the object of one’s jealousy. This snake yōkai and its associated metaphor are more often associated with the jealousy of women than that of men.

Slithering Sashes: Jatai (蛇帯)

Toriyama Sekien, "Kosode-no-te" from The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past, v.2 (Mist), c.1781, illustrated book, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York.

Want to browse more of these lesser-known monsters? Explore Toriyama Sekien’s The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past online through the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York. They have digitized their 3-volume set for easy, high-quality viewing at home!