Evolving Images: Ukiyo-e Monsters that Inspired Pokémon

Madison Folks

7/31/20257 min read

As the world of Pokémon nears its 30 year anniversary next year, let's take a look at the tales of a pop culture past that inspired some of the characters of this contemporary cultural juggernaut. From ukiyo-e monsters to "pocket monsters," here are four Pokémon that evolved from creatures far older than their franchise.

In Japanese folklore kitsune, or “foxes,” posses magical abilities and can assume human form, often favoring that of a beautiful woman. While the foxes we might spy in nature have a single tail, Japanese legends tell that kitsune grow additional tales with increasing age and power, reaching their ultimate ability with the ninth tale. Perhaps the most famous of these nine-tailed kitsune is known as Tamamo-no-mae.

With a history of prior imperial loves in China, Tamamo-no-mae resurfaced in Japan during the Heian period (794-1185) as the beloved concubine of Emperor Konoe. However, when the emperor’s astrologer discovered Tamamo-no-mae’s true identity as a nine-tailed fox, the emperor sent his soldiers to hunt her down and kill her. A later telling of this story states that after her death, Tamamo-no-mae’s spirit became trapped within a stone on the Nasu plain in today's Tochigi Prefecture. Known as the “killing stone (sesshō-seki),“ it was said to release toxic gas until the Buddhist monk Gennō Shinshō exorcised a repentant Tamamo-no-mae around 1389. In 2022, the tale took on contemporary relevance when the stone suddenly split in two. Though likely due to years weathering the elements, some remarked that Tamamo-no-mae’s soul had finally escaped the stone and a purification ceremony was performed at the site.

Turning to the Pokémon makeover of this vulpine spirit, the franchise expresses the idea of “more tails equals more power” quite literally. The six-tailed fox Vulpix—already a powerful fox if we go by the legend— evolves into Ninetails—the final evolution of this powerful fire Pokémon. But why the fire type? Perhaps this choice was due to the kitsune’s association with kitsunebi, or “fox fire.” Whether floating as will-o-wisps through the air, or hovering as a single flame blooming from the mouth or tail of the beast, the kitsune of legends possessed a fire magic similar to their Pokémon doppelgängers.

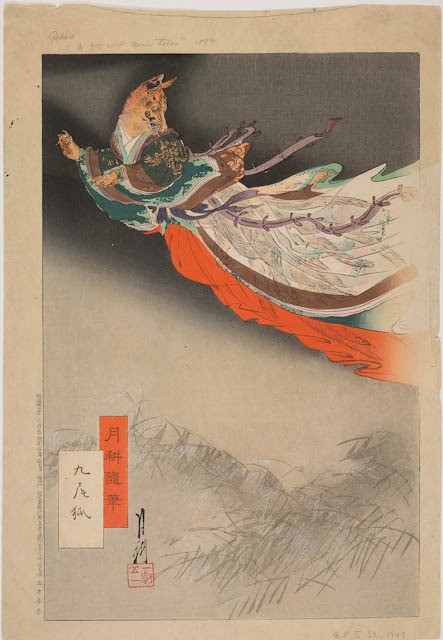

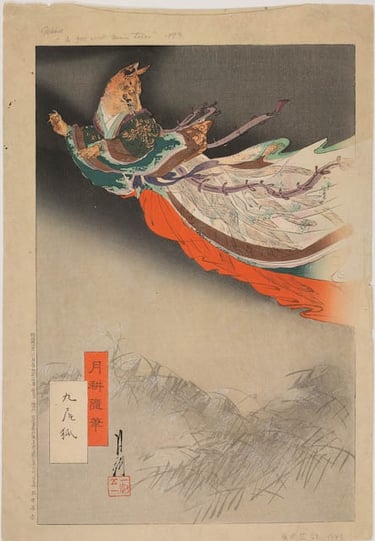

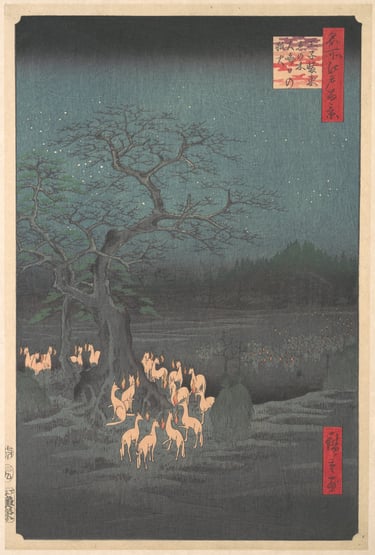

Fox Fire: Nine-tailed fox

Harukawa Goshichi (1776-1831), "Mirror with the Design of a Nine-tailed Fox," early 19th century, woodblock print, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York [view full record here].

(L) Ogata Gekkō (1859-1920), "A Nine-tailed Fox" from Gekkō Zuihitsu, 1899, woodblock print, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum [view full record here]. (R) Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), "Shozokuenoki Tree at Oji: Fox-fires on New Years Eve" from 100 Famous Views of Edo, 1857, woodblock print, Metropolitan Museum of Art [view full record here].

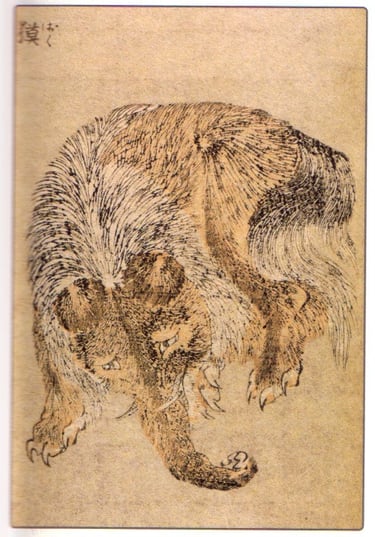

Originating in Chinese folklore, the baku entered Japanese tales as early as the 15th century. Legends state that once all other animals were created this mythical chimera was assembled from the spare pieces left behind—an elephant trunk, bear body, cow tail, and paws of a tiger. Though the baku's Chinese precedent and early Japanese iterations were said to deter illness, by the Meiji period (1868-1912) the baku had attained its power over dreams in Japan. At this time, stories tell that children could invite the baku to come eat their nightmares. However, children were warned now to overuse the baku’s services or else the creature would devour their hopes and positive dreams as well. In Japan today, tales of the baku and its taste for nightmares endure, though the monster has shed its chimeric appearance. Contemporary depictions resemble an animal of this world—a Malayan tapir.

The woodblock prints by Isoda Koryusai (1735-1790), Tachinbana Morikuni (1679-1748), and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) featured below reveal the shifting depictions of this beast in Japan. Koryusai and Morikuni’s baku bristle with ferocity—a feline body reminiscent of a leopard and a pair of tusks to go along with its trunk. Hokusai’s baku leaves a gentler impression. Set upon the legs of a tiger and body of a bear, the baku’s head features the rounded ears of a bear, miniature tusks, and a fuzzy trunk more akin to a tapir than an elephant. Personally, I'd rather run into Hokusai's baku in my dreams.

Looking to the world of Pokémon, Drowsy resembles this Meiji-period devourer of nightmares in both its tapir-like snout and skill set. Drowsy’s power is at its height when faced with a sleeping opponent. For example, the attack “dream eater” calls to mind the cautionary tales of famished baku eating a child's hopes and aspirations.

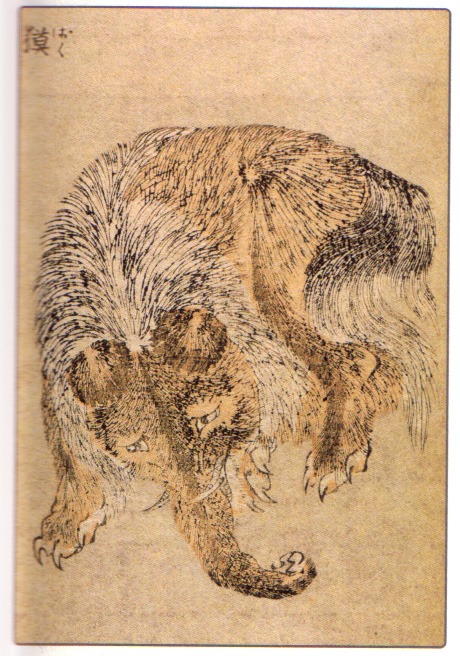

Dream Eater: Baku

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), "Baku" from Hokusai Manga, 19th century, woodblock printed bookpage, public domain, via wikimedia.

(L) Attributed to Isoda Koryusai (1735–1790), "Baku under Pine Tree," 18th century, woodblock print, Museum of Fine Arts Boston [view full record here]. (R) Tachibana Morikuni (1679-1748), "Baku; Boars," c.1740, woodblock print bookpage, Los Angeles County Museum of Art [view full record here].

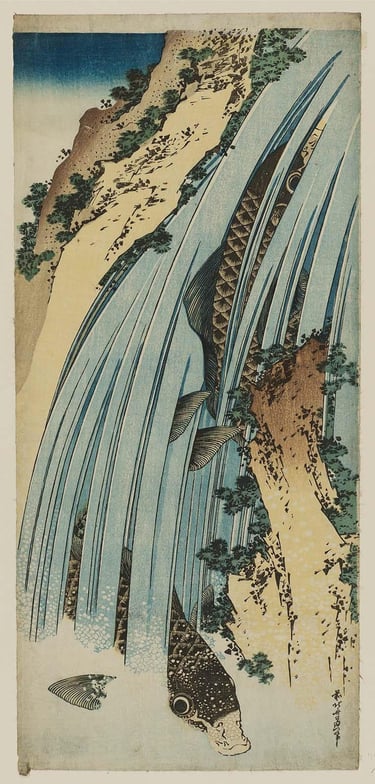

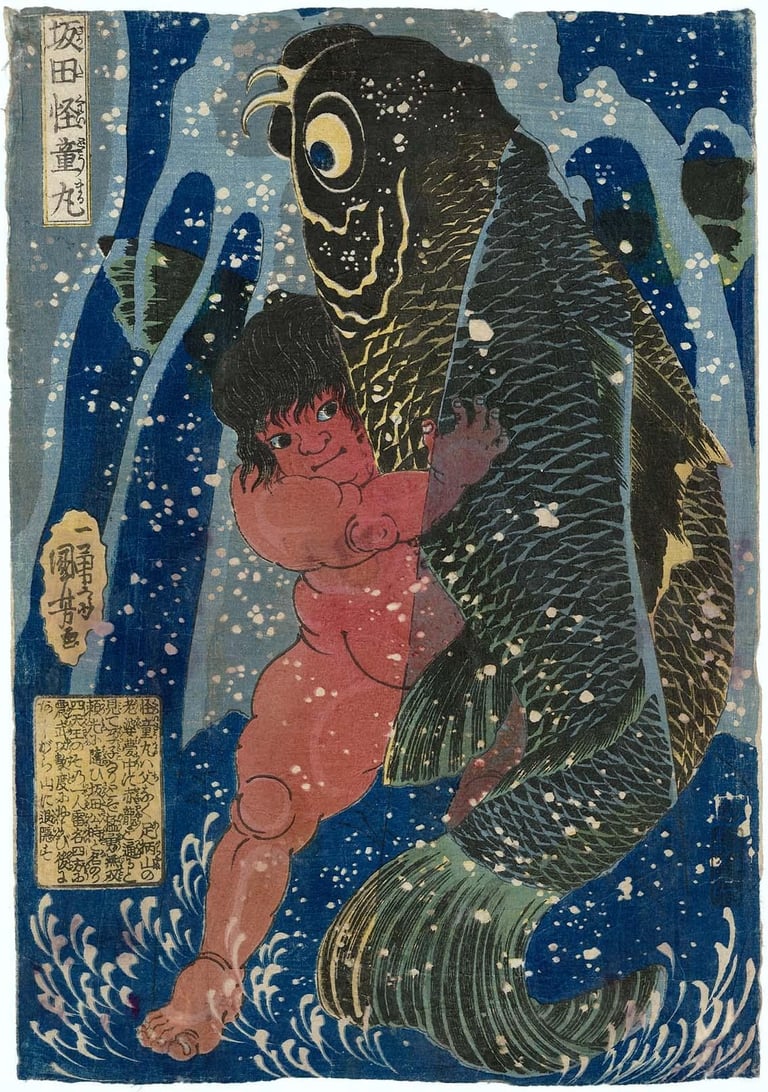

According to Chinese legend, a humble carp could transform into a dragon if it could swim up the rapids at Longmen (known as “the dragon gate”) on the Yellow River. At its origin, this story served as a metaphor for the passing China's top-level civil-service exam. In Japan, this tale of the carp's transformation rendered the fish a symbol of bravery and determination.

The image of a carp swimming up a waterfall can be found throughout Japanese woodblock prints, stenciled onto textiles, engaged in wrestling matches with the folkloric strong boy Kintaro, and fluttering as a banner in the May breeze. From the Edo period (1603-1868) through today, fluttering koinobori (carp-shaped banners) mark Boy’s Day (known “Children’s Day” post 1948). These koinobori represent parents' hope that their own children will be imbued with perseverance and diligence of the legendary carp.

In Pokémon, the evolutionary pair of carp-like Magikarp and the dragon Gyrados embody the carp’s mythical transformation through the dragon gate. While Magikarp may not face an upstream swim to evolution, Pokémon trainers must channel the perseverance and patience of legendary carp in order to level up their Magikarp and reach the evolutionary “dragon gate.” Their efforts are rewarded with a powerful water Pokémon, but the process is not for the faint of heart.

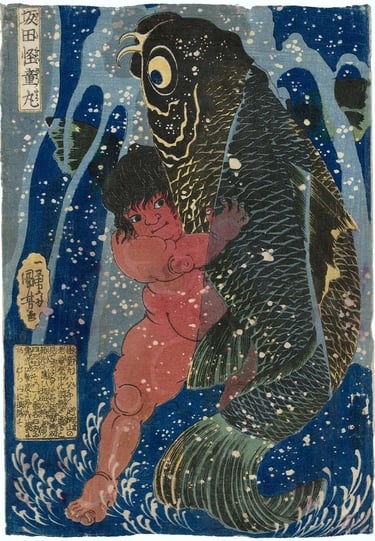

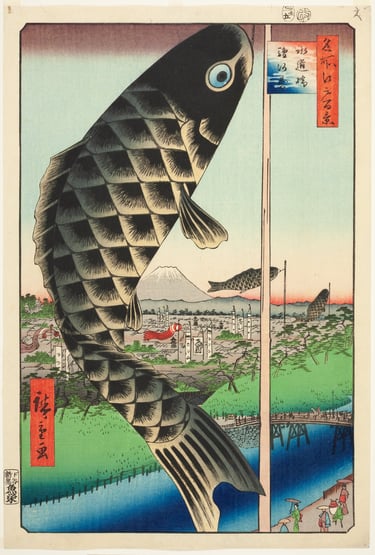

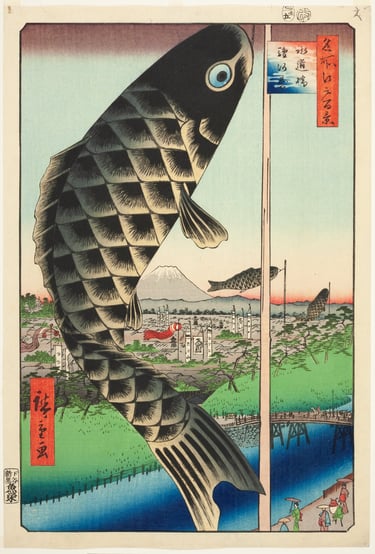

The Making of a Dragon: Crossing the Dragon Gate

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), "Two Carp in a Waterfall" c.1834, woodblock print, Museum of Fine Arts Boston [view full record here].

(L) Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), "Sakata Kaidōmaru," c. 1843-47, woodblock print, Museum of Fine Arts Boston [view full record here]. (R) Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), "Suidō Bridge and Surugadai" from 100 Famous Views of Edo, 1857, woodblock print, Art Institute of Chicago [view full record here].

The term namazu or onamazu refers to a legendary giant catfish held responsible for Japan's frequent earthquakes. Though this idea emerged as early as the 16th century, tales of the mischievous water-dweller reached a wider audience by the close of the 17th century. It was thought that the beast lived beneath the surface of the earth, subdued beneath a stone by a deity, yet, at times, the namazu overcame its keeper and thrashed about, roiling land above with earthquakes.

Following the devastating 1855 earthquake in the city of Edo, namazu-e, or “namazu pictures” became particularly popular. These woodblock prints ranged from talismanic images to humorous compositions rooted in the economic repercussions of these natural disasters. As the dust settled after an earthquake, the wealthy found their property damaged, while laborers found a windfall of work to repair that damage. For this reason, the namazu was sometimes called a “god of rectification” (yonaoshi daimyōjin) for this redistribution of wealth. A further reference to this social commentary can be found through the scattering of koban (gold coins) that appear throughout namazu-e.

As a ground and water type Pokémon with a rather catfish-like appearance, Whishcash aligns closely with myths of the namazu. In Japanese, Whishcash even has the name Namazun! According to the game, this Pokémon uses its fins to create earthquakes and can predict natural earthquakes before they happen. Though Whiscash may lack the social and economic implications associated with the namazu of legend, it carries namazu’s earthshaking abilities into battle.

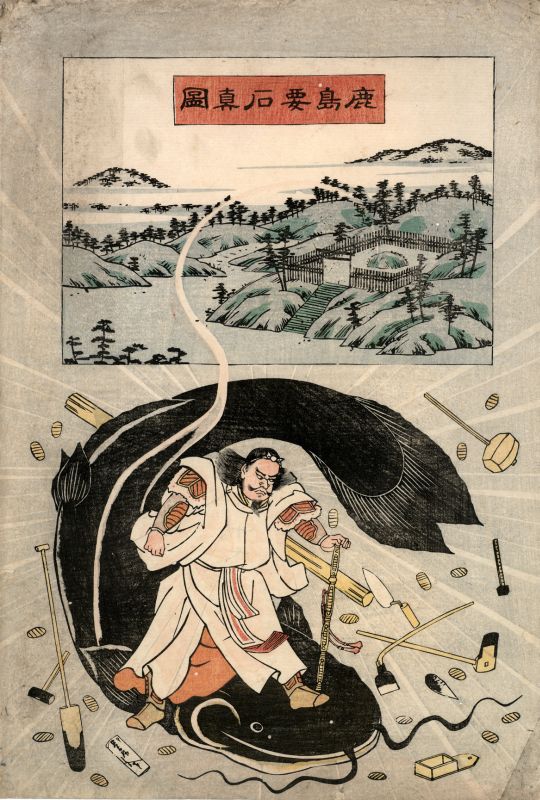

The Earth Shaker: Namazu

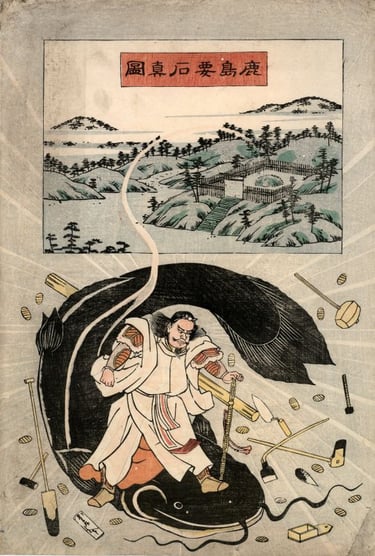

Unknown, "Kashima Foundation Stone's True Depiction," c.1855, woodblock print, Namazu-e Collection at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons [view full record here].

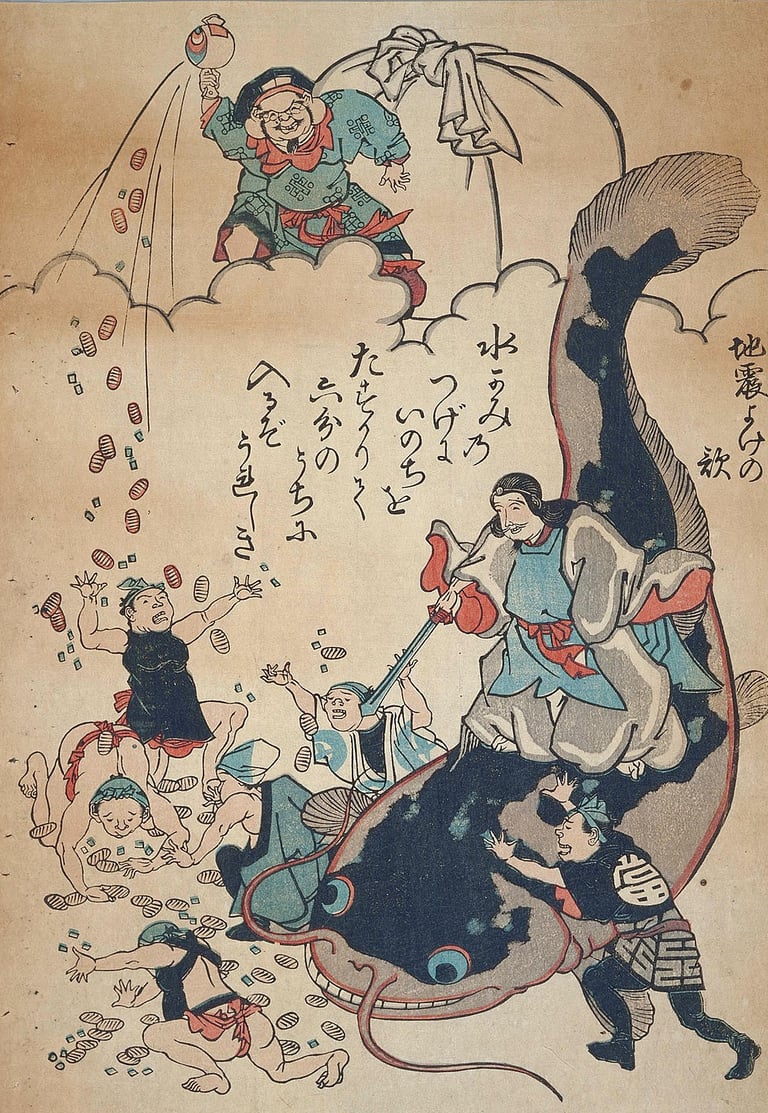

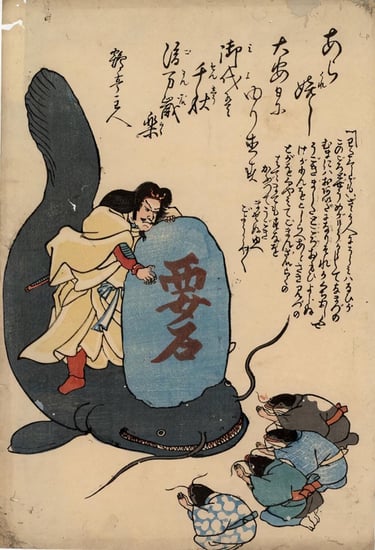

(L) Unknown, "Earthquake Averting Song," 1855, woodblock print, Waseda University Collections, public domain via Wikimedia Commons [view full record here]. (R) Unknown, "Takemikazuchi Okami Pins Catfish with Stone," 1855, woodblock print, public domain via Wikimedia Commons [view full record here].

Curious to learn more about Japanese woodblock prints? Discover more contemporary connections, hidden gems, and historical context through the blog.